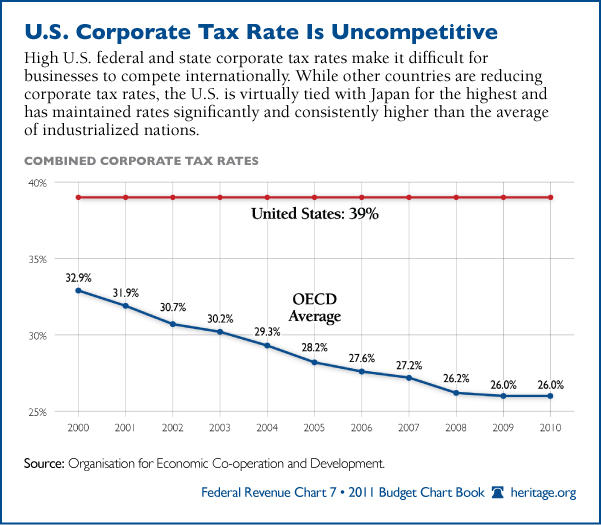

Last week, I focused on how the United States' unreasonably high corporate taxes can hinder American companies' global competitiveness, and Hostess Brands' monthly operating report (required for bankruptcy proceedings) shows at page 15 that the beleaguered company was/is responsible for not only state, local and federal corporate income taxes, but also millions of dollars in other taxes, including (i) Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA); (ii) Federal Unemployment Tax (FUTA);(iii) State/Local Unemployment Tax (SUTA); (iv) State/Local Business Licenses; (v) State/Local Sales Taxes; (vi) State/Local Use Taxes; (vii) State/Local Mileage Taxes; (viii) State/Local Real Property Taxes; (ix) State/Local Personal Property Taxes; (x) State/Local Vehicle Personal Property Tax; (xi) State/Local Accrued Franchise Taxes; and (xii) State/Local Accrued Operating Taxes.

Gee, is that all?

Of course, taxes aren't the only thing that can kill a company's bottom line - regulations hurt too, and as Henry Miller notes in a recent op-ed, they're getting increasingly worse:

Stultifying, job-killing regulation has been a hallmark of the Obama administration. An analysis by Susan Dudley, director of the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, reveals that with respect to "economically significant" regulations, defined as impacts of $100 million or more per year, Obama has been an outlier. While Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush "each published an average of 45 major rules a year ... the outliers are Reagan, who issued, on average, a mere 23 major regulations per year; and Obama, who has published 54 per year on average, so far."In the case of Hostess Brands, the most obviously relevant regulations are those laws which permit or favor "closed shop" rules that force workers to join a union and pay dues (as opposed to states with Right-to-Work laws that prohibit closed shops). It's difficult to quantify the costs that such closed rules impose on businesses and workers, but a recent examination of US job creation demonstrates that they could be significant (h/t Mark Perry):

And there are many more in the pipeline: According to Dudley, fully a third of the final major rules with private-sector impacts have been postponed. And the government's spring 2012 "Unified Agenda of Federal Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions," which provides a preview of and transparency with respect to agency and OMB planning for the coming year, still has not been published.

Since the recession ended in June 2009, almost three out of every four jobs added to U.S. payrolls have been in Right to Work states (1.86 million out of 2.59 million), even though those 22 states represent only 38.8% of the U.S. population (120 million). In contrast, only about one of every four new jobs were created in forced-unionism states (730,000), even though more than 61% of Americans live in those 28 states (189 million). Relative to their population, the Right to Work states have been job-creating powerhouses during the recovery, and forced union states haven’t even come close to “carrying their weight” in terms of their share of the population. Adjusting for differences in population, Right to Work states created four new jobs for every one job added in forced union states, because those 21 RTW states created 2.54 times more jobs even though forced union states have 1.6 times as many people.

Hostess Brands' problems provide anecdotal support for the above data on right-to-work versus closed shop states. According to the press release announcing Hostess' bankruptcy, existing union arrangements had crippled the ability to continue its business operations:

The [union] in September rejected a last, best and final offer from Hostess Brands designed to lower costs so that the Company could attract new financing and emerge from Chapter 11. Hostess Brands then received Court authority on Oct. 3 to unilaterally impose changes to the BCTGM’s collective bargaining agreements.These views find further support in several news reports which indicate that Hostess Brands' bankruptcy will likely attract several bidders for iconic labels like Twinkies because the new owners won't have to deal with existing union obligations:

Hostess Brands is unprofitable under its current cost structure, much of which is determined by union wages and pension costs. The offer to the BCTGM included wage, benefit and work rule concessions but also gave Hostess Brands’ 12 unions a 25 percent ownership stake in the company, representation on its Board of Directors and $100 million in reorganized Hostess Brands’ debt.

Daren Metropoulos, a principal of the Greenwich, Connecticut-based private equity firm, said of Hostess in an e-mail yesterday that ``shedding the complications of the unions and old plants makes it even more attractive.”In short, the company is only an attractive investment without the unions. Shocking, I know.

Tom Becker, a spokesman for Hostess, declined to comment on potential asset bids. While Hostess has seen interest in pieces of the business, its labor contracts and pension obligations have deterred offers for the whole company, Chief Executive Officer Gregory F. Rayburn said yesterday.

Unfortunately, even if Hostess Brands resolves the current union impasse through mediation, onerous labor regulations and obligations aren't the only thing raising the company's costs and hindering its competitiveness. In fact, US sugar protectionism is also putting a serious crimp in the company's (and other American bakers' and confectioners') bottom line:

Since 1934, Congress has supported tariffs that benefit primarily a few handful of powerful Florida families while forcing US confectioners to pay nearly twice the global market price for sugar.Unfortunately, congressional repeal of US sugar subsidies and protectionism doesn't look to be happening anytime soon; for example, the Senate in June voted 50-46 to maintain the sugar program in the new Farm Bill. Thus, even if mediation saves Hostess Brands in the short term, American sugar protectionism, as well as other onerous US regulations and taxes, could still prevent the company from regaining profitability and competing at home and abroad over the long term. As a result, Hostess - or a buyer of its most famous brands - could end up following many other US manufacturers facing competitiveness-crippling taxes and regulations:

One telling event: When Hostess had to cut costs to stay in business, it picked unions, not the sugar lobby, to fight.

“These large sugar growers ... are a notoriously powerful lobbying interest in Washington,” writes Chris Edwards of the Cato Institute in a 2007 report. “Federal supply restrictions have given them monopoly power, and they protect that power by becoming important supporters of presidents, governors, and many members of Congress.”

Such power has been good for business in the important swing state of Florida, but it has punished manufacturers who rely on sugar in other parts of the United States, the Commerce Department said in a 2006 report on the impact of sugar prices.

Sugar trade tariffs are “a classic case of protectionism, pure and simple, and that has ripple effects through other sectors of the economy, and, for all I know, the Hostess decision is one of them,” says William Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington....

[Congressional] refusal to address tariffs that neither support infant industries nor provide national security has come despite damning reports from the Commerce Department about the impact on US jobs, including the fact that for every sugar job saved by tariffs, three confectionery manufacturing jobs are lost.

Some of those job losses came when candy companies like Fannie May and Brach’s moved the bulk of their manufacturing to Mexico and Kraft relocated a 600-worker Life Savers factory from Michigan to Canada, in order to pay global market prices for sugar.

The impending mass layoffs from 33 Hostess plants scattered around the US, economists say, might force Washington to take a more serious look at how public policy affects the ability of corporations to make money – especially in an economy where even iconic brands like Twinkies and Wonder bread aren’t safe.

“I think there are policy implications here,” says Mr. Edwards, an economist at the conservative Cato Institute. “The Department of Commerce, the Obama administration, and [Congress] need to look at Hostess as a case study: Why did this company have to go bankrupt? Why were its costs higher than it could afford? Are there regulatory issues with import barriers on sugar or unionization rules that we need to look at and change? We’ve got to understand why manufacturing in a lot of cases doesn’t seem to be profitable anymore.”

[A]nother possible bidder hints at the future of Twinkies and maybe the US bakery business as a whole: Mexico’s Grupo Bimbo, the world’s largest bread baking firm, which already owns parts of Sara Lee, Entenmann’s and Thomas English Muffins.If Hostess or its new owners move offshore in order to avoid onerous sugar tariffs and other US regulations/taxes, Twinkies might indeed get that lifeline. Unfortunately, the thousands of Americans who used to make them won't be so lucky.

Bimbo has already sniffed around the bankruptcy proceedings that have haunted Hostess for a decade, in a bid to further expand its North American portfolio and pad its $4 billion net worth. Bimbo reportedly put in a low-ball bid of $580 million a few years ago, Forbes reports, and may be rewarded for that move since the Hostess kit-and-kaboodle may fetch more like $135 million today.

But the big question is whether the same problems that haunted Hostess – high sugar prices tied to US trade tariffs, changing consumer tastes, and union pushback against labor concessions – will squeeze whatever profit is left in the brands.

Especially if a Mexican buyer is involved, production may go the way of the Brach’s and Fannie May candy concerns: south of the border. With US sugar tariffs set artificially high to protect Florida sugar-growing concerns, a non-unionized shop with access to lower-priced sugar in Mexico could be the Twinkie lifeline, economists suggest.